Boeing employees raised concerns about 737 Max before crashes, documents show

A Boeing engineer was concerned that the troubled 737 Max, years before it came to market, had a flight-control system that lacked sufficient safeguards, according to a document released Wednesday during a tense hearing in the House where lawmakers hammered the manufacturer's CEO over two fatal crashes of the jetliners, and repeatedly asked why he hasn't resigned or given up his pay.

Other documents released during the hearing included a Boeing manager's concerns about the high pace of production at a Boeing 737 production facility months before the crashes, while another document highlighted assumptions about how quickly pilots could respond to a malfunction on board.

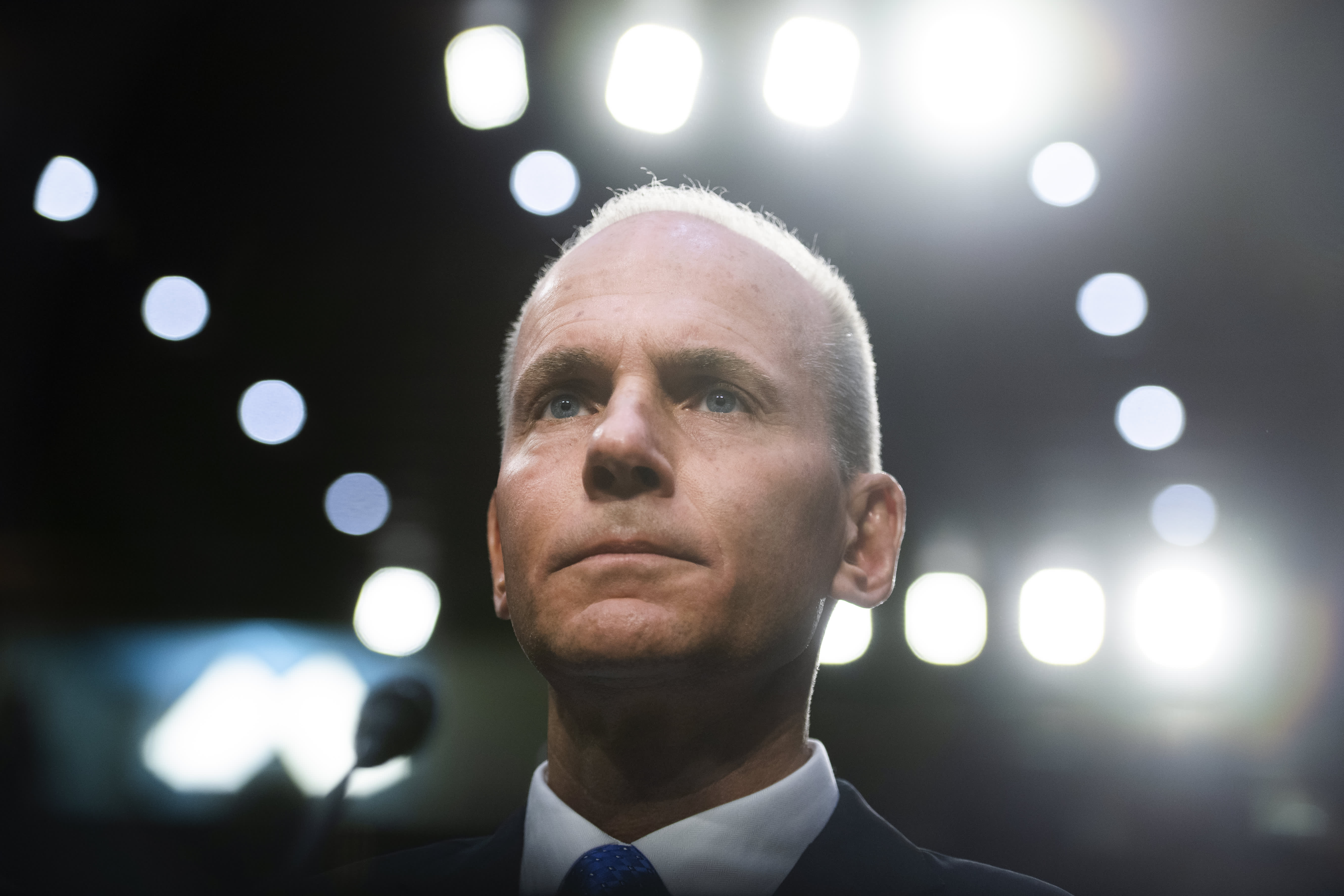

The more than five-hour hearing Wednesday capped two days of sharp questioning by lawmakers of beleaguered CEO Dennis Muilenburg on Capitol Hill this week. Those included calls that he forgo his salary this year and questions over why he hasn't resigned in the wake of the crashes that killed 346 people.

Muilenburg earned total compensation of just under $23.4 million for 2018, according to a Securities and Exchange Commission filing.

Boeing isn't handing out executive bonuses this year, a spokesman told CNBC.

The hearings underscored concerns that federal regulators didn't do enough to police the plane's design before they certified it as safe for passengers in 2017. They appearances also put Boeing's CEO on the defensive about flight safety assumptions and raised questions that the company prioritized profit over safety.

Crash victims' family members attended both hearings, holding up photographs of their loved ones at times. Muilenburg said he hasn't offered his resignation. He repeatedly said that his upbringing on an Iowa farm taught him to see the problem through.

When Muilenburg repeated his background, a group of victims' relatives said "go back to to the farm" during the hearing, the mother of one of the crash victims told the CEO after the hearing. "It has come to the point where you are not the person anymore to solve the situation," the woman told Muilenburg.

In one of the biggest revelations of the House hearing, in 2015, more than a year before the planes were certified by federal regulators, a Boeing engineer asked whether a flight-control system that was involved in both deadly crashes was safe because it relied on a single sensor.

Regulators around the world banned airlines from flying the planes after the crashes. Boeing has changed the planes' system so that they rely on two sensors instead of one. But regulators have not yet signed off on that and other changes the company has made to the planes, leaving them grounded for nearly eight months, which has crimped airline profits.

The sensors, which measure the angle of attack, or angle of the plane relative to oncoming air, feed an anti-stall system on the 737 Max. Erroneous data from a sensor triggered the system, known as MCAS, during the two crashes — one in Indonesia in October 2018 followed by another in Ethiopia in March. The crashes killed all 346 people on the flights.

"Are we vulnerable to single AOA sensor sensor failures with the MCAS implementation or is there some checking that occurs?" asked the engineer in a December 2015 email. The Federal Aviation Administration approved the planes in 2017 and they are Boeing's bestseller.

Source: U.S. Government

The email was obtained in an investigation of the planes by the House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, whose chairman, Rep. Peter DeFazio, D-Ore., said was the largest in the committee's history.

Chief engineer of Boeing's commercial airplane unit, John Hamilton, said the concern showed that the company's employees do raise questions "in an open culture" and that it was part of its "thorough process" to determine how many sensors to use.

But DeFazio asked why they didn't include data from two sensors earlier.

"If you can do it now … why didn't you do it from Day 1?" DeFazio asked Muilenburg. "Why not have that redundancy?"

Muilenburg responded, "We've asked ourselves that same question over and over and if back then we knew everything we know now we would have made a different decision."

The CEO added that Boeing intended to extend the capabilities of a system that had a history of more than 200 million safe flight hours.

"One of our principles is to take safe systems and then incrementally extend them," Muilenburg said. "We've learned since then, and that's how we've moved to this new design."

In another revelation, a manager of Boeing's 737 program said in a 2018 email that employees were "exhausted" while the company ramped up production of its biggest moneymaker to meet growing demand.

Because of the schedule pressures, employees were "either deliberately or unconsciously circumventing established processes."

"Frankly right now all my internal warning bells are going off," said the email. "And for the first time in my life, I'm sorry to say that I'm hesitant about putting my family on a Boeing airplane."

Muilenburg responded that he was aware of the email and those concerns and that the company took steps to address those concerns.

A separate Boeing document about MCAS from June 2018, four months before Lion Air Flight 610 crashed in Indonesia, warned that slow reaction times to runaway trim, which can push the nose of the plane down, could be "catastrophic" if pilots take more than 10 seconds to react and said it found a typical reaction time was four seconds.

Lawmakers and safety experts have criticized Boeing for underestimating the impact of a flurry of cockpit alerts on pilot response times.

Muilenburg, who has been CEO since 2015, also defended his staying in the job and declined to say whether he would give up his pay this year. The board stripped him of his chairmanship earlier this month. The company also ousted the head of the commercial aircraft unit.

"You're no longer an Iowa farm boy," said DeFazio. "You are the CEO of the largest aircraft manufacturer in the world. You're earning a heck of a lot of money, and so far the consequence to you has been, oh, you're not chairman of the board anymore."

Read More

No comments